Make a list of the twenty-first century’s truly momentous discoveries, and it’ll probably include big news stories like the existence of the Higgs Boson or the seductive allure of mom jeans. But the most important discovery of them all might be one that crept in without much fanfare: the idea that a person can’t think without their body.

This is not exactly a new idea (see: formerly fringe inventions of the twentieth-century like Feldenkrais, Pilates, and Montessori education). What is new is the fact that this idea has occurred to so many people in so many different forms, both within mainstream scholarship and without.

So why is this important? To understand the world, a body uses specific tools and signals: affective state, movement, position, touch. Missing here are the tools we usually ascribe to thinking: symbolic systems like language and logic. These two sets of tools are not mutually exclusive — we’re constantly using both of them, multimodally, joined together in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Part 1 of this two-part post traced an artistic development that dates back half a century: the realization that art could be more than just a purely visual experience. Today I’ll look at a similar shift taking place more widely, not just in the arts but in popular culture, politics, and social science. Like the artists who began thinking about perception as something that happens not in a pair of floating eyeballs but in a body moving through a particular space, our wider culture is finally acknowledging the limitations of semantic explanations for human experience (psychoanalytic theory, structuralism, even religion). Taking their place, increasingly, is a new attention to embodied phenomena: sensation, impression, orientation, affect, mood. Hovering at the edges of our awareness, these phenomena are, by their very nature, hard to put into words. But in everyday conversation they sometimes get lumped into one concept: vibes.

People tend to joke about vibes, but they’re a useful placeholder for certain invisible facets of human experience that defy rhetoric. Vibes help describe the ambient atmosphere of a situation. They help account for the magnetism of a person or the allure of a commodity. They help explain the mass behavior of voters and consumers. Vibes are antiphilosophical, nonverbal, irrational. Vibes can be ideological, but they are never logical.

Since the Enlightenment, symbolic thinking has taken priority over the bodily “passions”, but now this hierarchy is shifting, or maybe it’s just dissolving. The foundations of our society are being renovated. The lanes on the highway of life are being redrawn. It’s an exciting time to be alive. Also terrifying.

A STRUCTURE OF FEELS

Feelings are almost always framed as private, as things we experience inside our own bodies. But our feelings — and the feelings other people have about us — also affect us. They can limit our social horizons and restrict our actions. And when that happens, we’re no longer talking about just moods and perception but about access to material things: jobs, education, housing, healthcare, and therefore life itself. In this way, feelings create the social world we inhabit.

Much of the pioneering work on this embodied thinking has come to us though feminism and queer studies. “Feminist and queer scholars have shown us that emotions ‘matter’ for politics; emotions show us how power shapes the very surface of bodies as well as worlds,” writes Sarah Ahmed in her excellent 2004 book The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Also, importantly, “Such scholars have shown us how social forms (such as the family, heterosexuality, the nation, even civilization itself) are effects of repetition. As Judith Butler suggests, it is through the repetition of norms that worlds materialize.”

Queer studies is insightful here because it considers both non-normative bodies (gender variance) and non-normative orientations (of feelings like desire, pleasure, love). Simply for being yourself in a heteronormative society, you can be made to feel subordinate in a thousand different ways, from social exclusion to violence and imprisonment. As Ahmed says, “Such forms of discrimination can have negative effects, involving pain, anxiety, fear, depression, and shame, all of which can restrict bodily and social mobility.”

Shame stands out in this list, because it has the most explicit social valence. Shame, as a marker for what’s unacceptable in a community, is an essential component of our bond with others. More than just an interior feeling, shame burns across one’s entire surface, especially in the presence of others. Charles Darwin, in his 1872 book The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals, described this physical experience: “Under a keen sense of shame there is a strong desire for concealment. We turn away the whole body, more especially the shame, which we endeavor in some manner to hide. An ashamed person can hardly endure to meet the gaze of those present.”

The American psychologist Silvan Tomkins developed the notion of affects in the 1950s, and his work has become the foundation for a lot of contemporary academic interest in embodiment. Affects, he explained, are the neuro-physiological mechanisms that give rise to what we commonly understand as feelings and emotions. He ultimately theorized the existence of nine affects: two of them positive (interest-excitement and enjoyment-joy), one neutral (surprise-startle), and six negative (distress-anguish, fear-terror, anger-rage, contempt-disgust, dissmell, and shame-humiliation). Like Darwin, he posited an evolutionary origin for these pre-conscious mechanisms. In his telling, each negative affect emerged to help us avoid a different type of threat — a grizzly bear, for example, or a rotten sushi roll. To provide us with sufficient motivation to avoid that threat, the affect manifests itself as a punishing form of discomfort. As Tomkins put it, “All the negative affects trouble human beings deeply. Indeed, they have evolved just to amplify and deepen suffering and to add insult to the injuries of the human condition.”

The genius of queer liberation has been to defuse shame and replace it with a new kind of freedom. A lot of this work is achieved through the affirmation of queer community, where one can experience care and love without the misery of shame. The effects of this process are transformative, both personally and politically. It can instill people with a sense of agency, a capacity for action that opens new horizons of possibility — including the possibility of reshaping the entire social order. As Ahmed describes it, “Queer feelings may embrace a sense of discomfort, a lack of ease with the available scripts for living and loving, along with an excitement in the face of the uncertainty of where the discomfort may take us.” In other words, instead of simply coping with shame and discrimination, queer community offers liberation, even revolution.

When the artist Sharon Hayes, in her performance/installation Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time For Love? (2007), recites a hybrid protest speech / love letter to her (fictional) absent lover, her voice carries a longing for more than just reunion: “I’m trying to find a different way to talk to you. We have to forget the words we’ve known before. It’s impossible to learn how to speak to each other once and for all. Almost everything has to be re-envisioned, has to be rebuilt anew.”

Gay liberation in the US began with acts of public resistance like the Stonewall uprising. And the movement has been in motion ever since, via pride parades and dyke marches. These events are typically spoken about in terms of visibility, but their real power may be the physical charge they give their participants, delivering on a potential so often denied them in daily life: to dress and act as they desire, to move freely, to take up space.

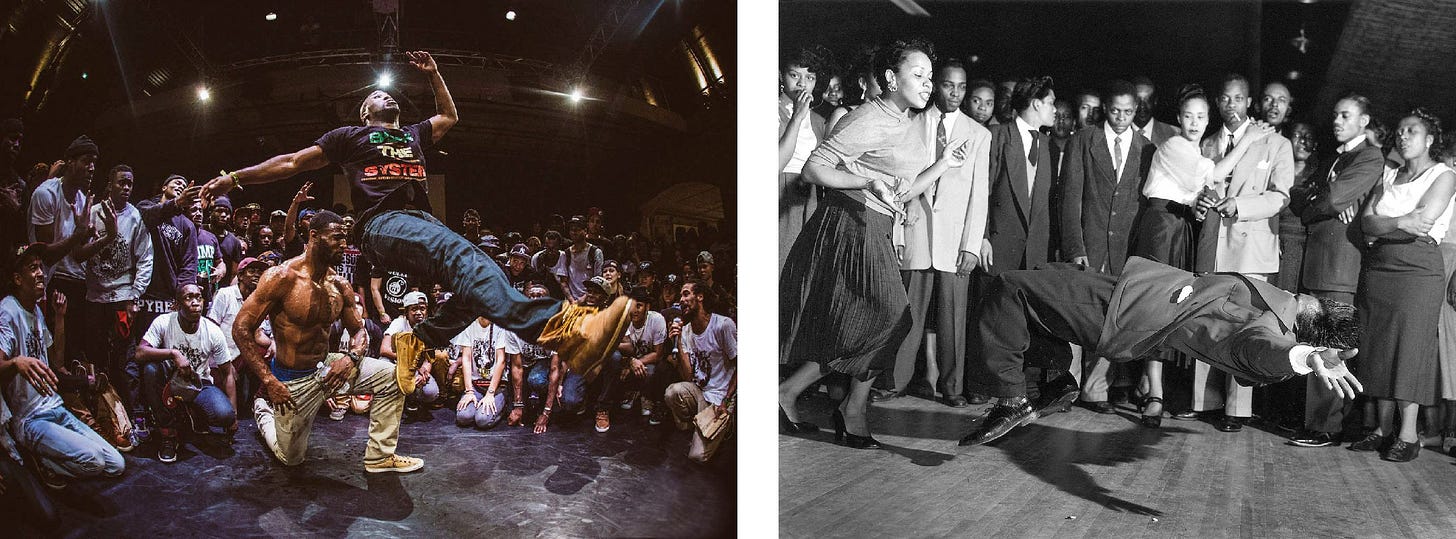

This celebration of agency in the face of subordination creates the collective self-confidence that powers many subcultures. Subculture isn’t even the right word when we’re talking about something that has risen to the top of our mass culture. Twenty-five years ago, asking a DJ “Could you play something with more of a vibe?” was a polite way of saying, “Your music sounds too white.” (Reader, sometimes I was that DJ.) Vibe, the first hip hop magazine, was launched in 1993, and when we use that word today (which is often) it retains many of its connotations from 1990s Black American culture. Consider the dozens of rappers and R&B singers who currently perform under the name Vibe (or V.I.B.E. or Vibe$ or Vybez). Or just listen to Apple Music’s Vibes playlist, which delivers “mood and texture” in the form of recent downtempo house with R&B vocals (e.g., Kelela, Sampha).

Music is a good way to understand this shift toward embodied perception. It’s invisible, immaterial, and literally made of vibrations. And it can affect the body in ways that transcend language or even awareness. Anyone who has danced with tears in their eyes understands this. Ever since the arrival of radio and recorded music, many if not most of the world’s popular musical styles have been based on Black American music. As Ashon Crawley wrote in his 2015 essay “Otherwise Movements”, “The beauty in Black music is found in how it releases what was compressed in its seed with such intensity, with such vibrational force. The beauty is in what was always there in potential, in the capacity it held to be multiple.” The compression he describes, this product of centuries of subordination and ongoing social, physical, and psychic brutality, creates the conditions for a release of vibrational force so powerful it can transform the inner lives of people all over the planet. Now that is a vibe.

In Crawley’s account, this vibrational force achieves its peak revolutionary dynamic when it’s at its most embodied: in dance. Collective physical movement can take us far beyond the limits of rhetoric, rationality, and traditional political strategy, blazing an uncharted path he calls otherwise than. “This otherwise than strategy is sight, sound, touch, taste, smell working together in varied degrees based on the abilities given to each of us as gift to perceive the worlds we inhabit. […] This demand for change, change that is founded in movement, in vibration, produces a critique of the normative world.” Here again we find the liberating power of enacting the potential denied elsewhere in life: the capacity to behave as one desires, to move freely, to take up space: “In Black social dance is a restive quality, a refusal of being stilled. And this refusal of being stilled is how change occurs, through nuance, through style.”

Unfortunately, the transformative power of embodiment doesn’t belong to oppressed groups alone. There’s a similar operation underway at the other end of the social spectrum. And, I’m sorry to say, it doesn’t involve music, sex, or dancing.

THE DARK SIDE OF THE FEELS

During the hours and days after the 9/11 attacks, New Yorkers experienced a collective surge of compassion like nothing I had ever felt before. Suddenly, in this city of eight million strangers, there was no emotional distance separating us. Random subway riders offered me reassuring glances. Longtime neighbors checked in on each other for the first time. Taxi drivers stopped honking their horns. When this powerful fellow-feeling began to fade a couple days later, the psychic barriers went back up. And that’s when the American flags began to appear.

At first the flags felt like symbols of our collective grief and vulnerability. (My friend spontaneously baked a flag cake, much to her astonishment.) But a flag doesn’t just unite. It also divides. Very quickly, the ambient compassion gave way to declarations of us versus them and conversations about the scale of “our” military response. Collective vulnerability, it turns out, is not a comfortable place for many Americans.

Legal and military experts have long complained about the word terrorism: “The term is imprecise; it is ambiguous; and above all, it serves no operative legal purpose.”

Terror-fear is one of Silvan Tomkins’s six negative affects. And you can’t defeat a subjective neuro-physiological reaction with military force. But we ended up with a War on Terror anyway. Solemn leaders standing at their podiums aligned our nation with the attack’s 3,000 victims, and an overwhelming majority of Americans aligned themselves with the nation and its leaders. Immediately after 9/11, George W. Bush’s approval rating jumped from 51% to 90%, and every flat surface in the country suddenly had an American flag plastered on it. It was Pride Month, basically, but instead of rainbow flags and hot pants we got the stars & stripes and fighter jets.

How was the patriotism that surged after 9/11 different from the love that spontaneously emerges from any disaster? In a word, hate. Patriotism is love with a hard boundary. It’s a passionate alignment with a specific set of people and against another. And in those months and years following 9/11, the boundary around “America” was no longer just the nation’s border but also a psychological and political boundary that excluded entire communities of American citizens, namely Muslims and anyone who “looked” Muslim (which at various points included Sikh Americans, Hindu Americans, Latino Americans, Black Americans — basically anyone who had a skin tone darker than milk and a name that wasn’t Heather or Jeff). If you fell into one of those categories, you were considered a potential threat and treated accordingly. Sarah Ahmed describes how this process works in The Cultural Politics of Emotion: “The ordinary white subject is a fantasy that comes into being through the mobilization of hate as a passionate attachment closely tied to love. The emotion of hate works to animate the ordinary subject, to bring that fantasy to life, precisely by constituting the ordinary as in crisis, and the ordinary person as the real victim. The ordinary becomes that which is already under threat by the imagined others whose proximity becomes a crime against person as well as place.”

Two decades later, we’re witnessing a similar panic around (non-white) immigrants. And Ahmed’s description from 2004 remains depressingly accurate: “The politics of fear is often narrated as a border anxiety: fear speaks the language of ‘floods’ and ‘swamps’, of being invaded by inappropriate others, against whom the nation must defend itself. […] Indeed, it is fear of death – of the death of oneself, one’s loved ones, one’s community and one’s people — that is generated by such narratives as a means of preserving that which is.” In other words, when someone stokes fears of an imaginary invasion, they simultaneously define and maintain the status quo.

Along with fear-terror, another negative affect is relevant here: contempt-disgust. Research in the past decade has demonstrated a clear link between prejudice toward ethnic out-groups and an elevated sensitivity to disgust. Biologists and behavioral scientists think this disgust toward outsiders my have arisen as a protection against contagious pathogens. But whatever the reason, it’s useful to know that many of our fellow citizens experience physical proximity to any member of an out-group as punishingly unpleasant.

The phenomena I’ve been describing here are, to put it mildly, very bad vibes. We as a society view ethnic, racial, and religious prejudice as unacceptable. We see hate crimes as, well, crimes. Our country has made some (halting) progress in confronting its long history of racism and misogyny, and for several decades there has been broad agreement that our moral arc is bending toward acceptance and even celebration of the pluralistic democratic society we live in.

Meanwhile, in the same America, a bunch of people with money and political connections — a.k.a. the status quo — look at bad vibes and see an opportunity. When the Republican Party curdled into its current form in the 1970s, it did so by centering fear and disgust. This turned out to be a winning formula, not just here but also in Europe, Latin America, and across the globe. In this formula, fear and disgust are always framed in terms of love, patriotism, and a valiant defense of the family (understood here to be white, Christian, cisgender, heterosexual). It’s a form of solidarity based on insecurity, on the shared fantasy of a threat to one’s racial superiority, one’s children, one’s home, one’s religion, one’s vehicle, one’s guns. The border is how these people define themselves, and securing it becomes their priority. (Stephen Miller’s “America is for Americans” speech at last Sunday’s Trump rally is a pure distillation of this Hitlerian messaging.)

These feelings aren’t based on a coherent political ideology, much less a functioning theory of government. They are powerfully visceral and, most importantly, highly motivational. But they’re also volatile. In the 1970s and 1980s, Republican leaders needed to figure out how to harness this power for their own ends without transgressing the norms of respectable political discourse. So they coded their racism, promising to rein in “welfare queens” and “gang bangers”. But the real breakthrough arrived in the 1990s, in the sphere of entertainment — sorry, infotainment.

Rush Limbaugh gets credit for discovering the One Weird Trick that has supercharged the Republican party. Turns out by vocalizing people’s hate, fear, and contempt for disfavored out-groups — not just acknowledging those negative feelings but joking about them, enjoying them, embracing them — you can turn those people into your followers for life. They will vote against their own self-interests again and again, just to be part of a community where those dishonorable feelings are affirmed without shame. “Shame is the affect of indignity, of defeat, of transgression, and of alienation, striking deep into the heart of the human being and felt as an inner torment,” wrote Silvan Tomkins. When that inner torment is finally lifted, how does a person feel? Relieved. Joyful. Triumphant.

YOUR FEELINGS ARE A BATTLEGROUND

Political scientists and strategists have always struggled to understand voters’ behavior. When television transformed politics in the 1960s, political journalists employed the term charisma to explain how candidates like JFK and RFK had an uncanny ability to motivate voters not with ideology or policy but with the sheer force of personality.

This brings us to the Democratic Party’s current motivation problem. In the twenty-first century’s six presidential elections, there have been only two resounding Democratic victories. In both cases, the candidate was Barack Obama. That man has charisma for days, and his election represented a uniquely uplifting milestone in our history. In other words, the vibes were immaculate. He even received millions of votes from future Trump voters.

But political pundits on the center and the left continue to insist that voters are primarily motivated by policy and its material impact their everyday lives. Economic insecurity is a legitimate fear for most voters, this thinking goes, and if you make people’s lives more secure, they’ll be less susceptible to rightwing manipulation. As much as I agree with this theory, in the context of runaway wealth inequality there’s no viable path for a politician to deliver financial security for a majority of voters before the next election. Even the current administration’s reversal of the worst recession in nearly a century has failed to earn Biden any political credit. In a June 2024 poll, 59% of respondents said the US economy was still in a recession, despite all evidence to the contrary. There’s even a word for this misalignment of perception and metrics: vibecession.

Economists and political scientists began leaning on the concept of vibes in 2021, first as an acknowledgment that their models of human behavior were no longer sufficient. As Will Stancil wrote in his 2021 essay “Vibes in Politics”, “It means thinking about emotions, instead of reducing voters to rationally self-interested economic actors. People are driven by emotions, and a lot of what we do is a pretext for expressing or resolving emotional states or urges that lie a lot deeper than our conscious rationales. ‘Winning the argument,’ a popular tactic especially among liberals, seems unlikely to be productive because it doesn’t actually affect these emotional drivers.”

Stancil partly ascribes this phenomenon to our current information environment: a robust rightwing media machine headed by Fox News, a shrinking sector of performatively neutral news organizations, and a steady drift toward social media as a chaotic source of political news. His advice to Democrats: “Fill all the space available to you with the most potent messages possible.”

This may require ditching the party’s old messages (“Bipartisan tax credits to anyone who opens a small business in a designated Economic Recovery Zone!”) and replacing them with messages that will trigger a highly motivational neuro-physiological reaction. In a world where multiple nuclear powers are at war, an American fascist party is on the rise, billionaires are destroying public education, and a global climate crisis threatens life on Earth, they should be able to come up with something! As the Republican Party has proven repeatedly, you don’t even need to impress voters with workable policy proposals. The indispensable first step is motivating voters. Then, once you’re in a position of real power, you’ll have the political space for your policies to evolve into effective legislation. And then one day you might solve enough real problems to make life in America slightly less miserable for everyone.