Unintended Consequences

Speculation helps us decide how we want to live. And because we live together, whether we like it or not, we speculate together. Darkforum is me speculating about the present, via the future and the past. This first post examines why you can’t avoid downstream effects by simply refusing to contemplate them. And why, actually, we all live downstream.

Edmund Carpenter was an American anthropologist who established the field of media studies with Marshall McLuhan. In 1969 and 1970 Carpenter researched how the spread of radio, film, and television would affect bands of hunter-gatherers living in the distant swamps and mountain valleys of Papua New Guinea. These groups, who still used stone tools and spoke more than seven hundred distinct languages, lived in almost total isolation from the modern world.

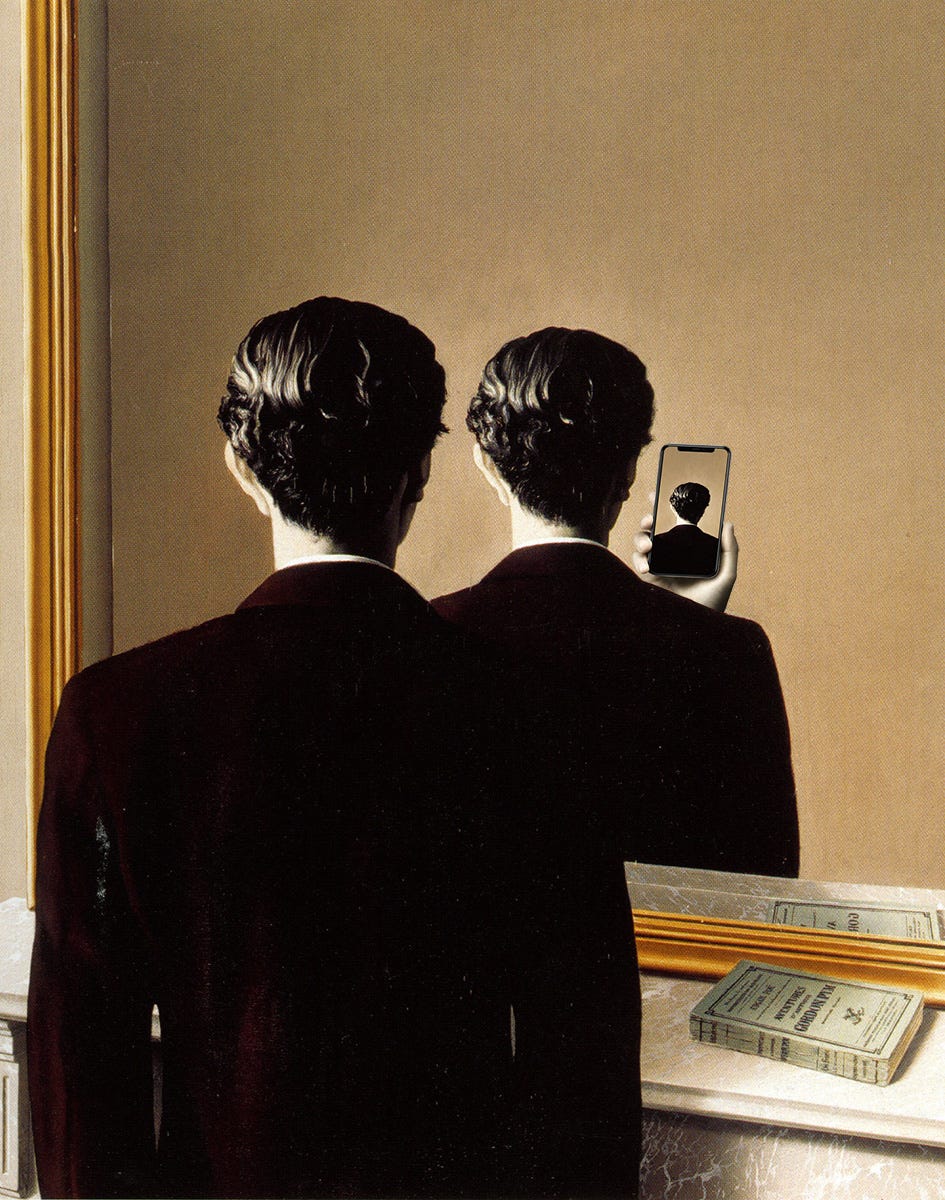

Carpenter’s experience there would ultimately trigger a crisis of faith in anthropology. At the time, Papua New Guinea was still a colonial territory, and his research was underwritten by the Australian government, whose objective, he soon realized, was to exert political control over these groups, not to preserve their culture. Still, as Carpenter reflected later, “I accepted the assignment because it gave me an unparalleled opportunity to step in & out of 10,000 years of media history. I wanted to observe, for example, what happens when a person — for the first time — sees himself in a mirror, in a photograph, on film; hears his voice; sees his name.”

Here in the United States, conservative pundits and libertarian economists spend a lot of time thinking about public policy and its unintended consequences: Social programs for alleviating poverty actually spread poverty. Welfare undermines the family and the church, increasing the need for welfare. A minimum wage is counter to workers’ interests. (With the unregulated self-assurance of a free-market economist, Milton Friedman phrased it this way: “Minimum wage laws are about as clear a case as one can find of a measure the effects of which are precisely the opposite of those intended by the men of good will who support it.”)

These arguments have all been refuted, repeatedly. But they still hang around. In fact, the same rhetorical claim — that whenever the government tries to improve society it achieves the opposite — has been used to attack social programs for more than two hundred years. Back then, this rhetoric was used against policies like expanding the right to vote, which, conservatives insisted, would trigger the blood-soaked demise of Western civilization. (Their predictions didn’t pan out. But when you’ve written a hit song, you keep it on your set list.)

For these same economists and pundits, meanwhile, private enterprise gets a free pass. Which is strange, because free enterprise accounts for more than three quarters of the economy. And its unintended consequences are far more widespread and ruinous (a few of its recent casualties: independent stores, local journalism, affordable rents, secure employment, polar ice sheets). If conservatism is all about maintaining traditional values and customs, such cataclysms are the opposite of conservatism.

But if conservatism is actually about maintaining power, this kind of destructive change is not a negative side effect at all — it’s a smart business strategy, a proven mechanism for amassing wealth and influence. Disruption is good for outpacing regulation, undermining workers, and cornering a market. Just ask AirBnB, Amazon, and Uber.

Visiting an isolated band of hunter-gatherers who had never encountered a mirror, let alone modern media, Carpenter and his team shot Polaroid photos of some male villagers. When each man was handed his portrait, he reacted in the same way: “Recognition gradually came into the subject’s face. […] We recorded this over and over again on film, including men retreating to private places, sitting apart, without moving, sometimes for up to twenty minutes, their eyes rarely leaving their portraits. […] In particular, we recorded the terror of self-awareness that revealed itself in uncontrolled stomach trembling.”

On Carpenter’s next visit, several months later, he found the villagers transformed, scarcely recognizable. “They carried themselves differently. They acted differently. […] In one brutal movement they had been torn out of a tribal existence & transformed into detached individuals, lonely, frustrated, no longer at home — anywhere. I fear our visit precipitated this crisis. Not our presence, but the presence of new media. […] The effect was instant alienation. Their wits & sensibilities, released from tribal constraints, created a new identity: the private individual. For the first time, each man saw himself & his environment clearly and he saw them as separable.”

Not long ago, Facebook’s stated mission was, famously, to break things. Twenty years later, we’re still discovering what social media has broken. So far it has shredded our attention spans, public discourse, mental health, and shared sense of reality. Some of the blame rests with the algorithms tuned to increase user engagement, which thrives on conspiracy theories and other topics that happen to be terrible for society. Recent studies, though, suggest there’s something inherent in social media that increases feelings of loneliness and alienation, with serious side effects for individual mental health. I’m not just talking about tweens on TikTok. Consider what Nextdoor has done to suburban adults.

And how has the tech industry responded? By offering us immersive tech goggles.

The history of new communication technologies, from the printing press to the radio, is a tale of centuries-old traditions of social conduct overturned almost overnight. Right now, brilliant academics and journalists around the world are churning out analysis of the tech industry’s latest innovations and their effects on individuals and society. They’re uncovering the tendency of face-recognition systems to reinforce structural biases like racism. They’re documenting the hazards of self-driving cars. They’re uncovering high-tech tools used by authoritarian regimes to silence critics and persecute minority groups.

Most tech companies, though, remain aggressively ignorant, if not downright hostile, to the unintended consequences of their innovations. Technological progress is an unstoppable force, they insist. Their company must harness its power for the good of humanity (while reaping record profits) or else some villain will seize it for evil (China!). The company’s internal critics will be silenced or fired, external critics discredited or ignored. Development can’t pause to consider a product’s negative impacts. Too much money is at stake. Anyway, comms professionals and lobbyists will ensure that the company’s narrative of inevitability dominates the public conversation.

When it comes to messaging, though, artificial intelligence presents a unique problem. Its consequences have already been contemplated for centuries, from Frankenstein to 2001: A Space Odyssey and Black Mirror. If these works of fiction ever slowed down AI development, that effect has largely worn off. Tech titans have demonstrated (repeatedly) that they don’t understand the potential side effects of their creations. As their public statements confirm, they lack the speculative capacity to imagine a future beyond their own glorious exit. For self-styled tech visionaries manifesting a better future for us all, this deficiency of imagination is a big liability. One shortcut they’ve developed is to build their pitch around an idea from science fiction. This move works for the same reason a music producer might sample the hook from a 1980s hit. The idea has been in everyone’s head for so long, it already feels real. It seems inevitable, rather than just one among infinite possibilities.

But what if the sci-fi tech your product most resembles is a homicidal robot? Do you step back and consider the implications? Not if you’re a founder. Instead you launch a multilevel PR campaign, seeding news outlets with innocuous stories about AI’s beneficial applications, from diagnosing cancer to improving your mapo tofu recipe. At the same time, you twist the portents of doom to your advantage by lobbying Congress for regulations that will crush your smaller competitors, because only YOU can be trusted with Skynet. (In case you haven’t noticed, “good guy seizes magical object before villain” is also the plot of every single Indiana Jones movie.)

So… AI is a tool that could destroy life on earth, but in the meantime it will help you plan your next family vacation? Honestly, the unintended consequences of this technology probably won’t include homicidal machines killing humans and turning the earth into an uninhabitable wasteland. (Granted, AI is already helping armies murder civilians at scale. And it is making the world less habitable, thanks to its exponential thirst for water and energy.) In the short term, at least, AI’s most likely unintended consequences will be precarious employment and a tsunami of spam. In other words, it will make familiar problems even worse for most of us — less Terminator 2, more I, Daniel Blake.

In one village, Carpenter’s team filmed a traditional initiation ceremony for young men. “The elders asked to have the sound played back to them. They then asked that the film be brought back & projected, promising to erect another sacred enclosure for the screening. Finally they announced that this was the last involuntary initiation & they offered for sale their ancient water drums, the most sacred objects of this ceremony. Film threatened to replace a ceremony hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years old[, because] now the ceremony, and by an extension the entire society, could be put on a screen before them, detached from them. They could watch themselves. No one who ever comes to know himself with the attachment of an observer is ever the same again.”

Long before science fiction, people began speculating about our individual future — what happens when we die? The question is central to most of the world’s religions (which came up with some pretty wild explanations) and our greatest works of literature. How do we live, and love, with death looming over us? The answers vary, but most of them agree that death is what makes life precious, what gives it meaning. When a human character is granted immortality, it usually turns out to be a curse.

No surprise, then, that the tech industry is here to disrupt death.

Interestingly, the argument used by conservative pundits against minimum wage laws (the arrogance of any government that thinks it can improve citizens’ lives will yield the opposite outcome) has the same ancient root as movie vampires bemoaning their immortality. Greek mythology is filled with stories of mortals punished for their hubris. When Aeschylus established the genre of tragedy 2,500 years ago, many of his plays employed that same storyline, and since then it has become one of our most satisfying plot mechanisms, from Macbeth to Jurassic Park.

If you took only STEM courses in college, this may be news to you. In fact, if you’re a successful Silicon Valley founder basking in your overconfidence and entitlement, you probably hear only the word hero in tragic hero. But the thing about sci-fi and other speculative fiction is that it’s not actually about cool future tech. Like all literature, it’s about the characters and their social world — “our thoughts and our dreams, the good ones and the bad ones,” as Ursula K. LeGuin put it. “It seems to me that when science fiction is really doing its job, that’s exactly what it’s dealing with. Not ‘the future’.”

Social change is unavoidable. Our way of life isn’t perfect — there’s a lot of room for improvement. And this is where we bump up against the conservative pundits and libertarian economists. For them, destructive change is actually fine, as long as it moves in a direction that advances their interests (fewer restrictions on businesses, lower taxes on the rich) while reinforcing the current structure of wealth and power.

Just like public policy, the impacts of a new technology are unpredictable. But no technology is immutable. It changes over time and, more importantly, so does its role in a society. Its conception and implementation should, ideally, be transparent, guided by professional ethics and a sense of public responsibility. But even after a company has locked us out of the development process and shipped the product, we still have a voice in how it gets used. Silicon Valley would like us to think technological innovation is a force of nature. It’s not. Like other messy and infuriating things in life, it’s a social process. Its meaning is never really settled.

Of course, standing up to something that’s backed with so much money and influence isn’t easy. It will always be a fight, with efforts coordinated on multiple fronts. Fortunately, history is filled with examples of societies choosing their own future, from the rejection of slavery in pre-1700 coastal California to the prohibition on human-cloning research in late-1990s North America and Europe.

Two years after abandoning his research in Papua New Guinea, Edmund Carpenter published Oh, What a Blow That Phantom Gave Me. He considered the book a warning — such was the destruction he had witnessed, of individual minds and entire cultures. “It will immediately be asked if anyone has the right to do this to another human being, no matter what the reason,” he wrote. Indeed, his field work in Papua New Guinea was soon criticized by anthropologists such as Clifford Geertz. And their criticism was absolutely correct — Carpenter’s experiments were a breech of professional ethics. But his critics may have overlooked the central point of his book: that what he did to these hunter-gatherers paled in comparison to the spread of commercial electronic media on a global scale, a process already long underway, with no consideration for its unintended consequences. What gives anyone the right to do this? “If this question is painful to answer when the situation is seen in microcosm,” he wrote, “how is it answered when seen in terms of radio transmitters reaching hundreds of thousands of people daily, the whole process unexamined, undertaken blindly?”