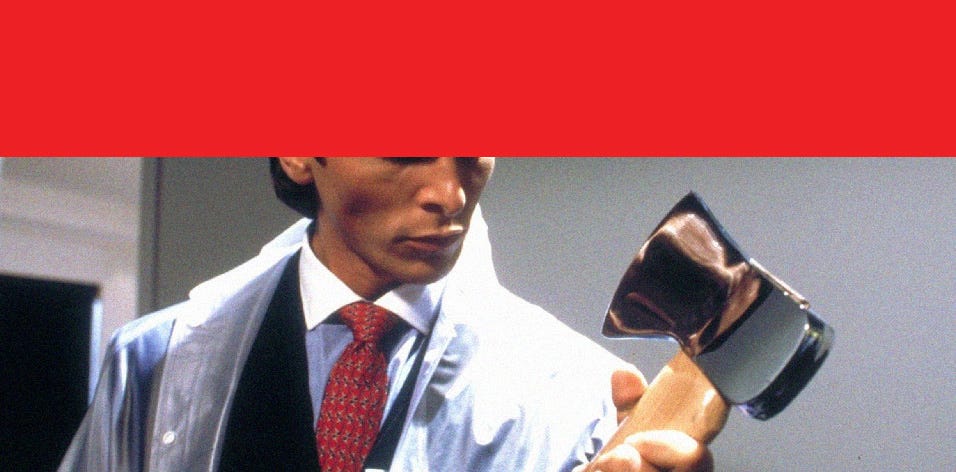

These days you hear a lot about narcissists. Not so much about psychopaths. Everybody seems to have a narcissist in their dating history or their immediate family — probably because we finally know how to spot one, maybe also because there are more of them around. But the psychopath has a longer history, first capturing America’s imagination in the 1950s as a stock villain in popular movies and novels before making the jump to the evening news in the 1960s.

Psychopaths are social predators, first and foremost. They live to take advantage of other people — mentally, physically, financially — and they do so without remorse, because they have no empathy and no conscience. But neither do malignant narcissists. A narcissist doesn’t care about other people’s feelings, and rules don’t apply to him. (I’m using masculine pronouns because these disorders are most prevalent in men.) All his deceitful manipulation, however, serves a different objective: affirming his own superiority via the admiration of others. Unlike the psychopath, who often works in the shadows to evade detection, the narcissist uses attention to numb his psychic wounds. Which means he always needs an audience, the larger and more submissive the better.

In what I’m about to say on the work of Cady Noland it’s important to remember that, aside from this one distinction, the narcissist and the psychopath exhibit the same key traits: ruthless dominance, insatiable aggression, and calculated cruelty.

“There is a meta-game for use in the United States. The rules of the game, or even that there is a game at all, are hidden to some. The uninitiated are known as naïve, provincial, suckers. To those unabused by an awareness of backdoor maneuvering, a whole world of deceit remains opaque. Those in the dark are ripe for exploitation.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

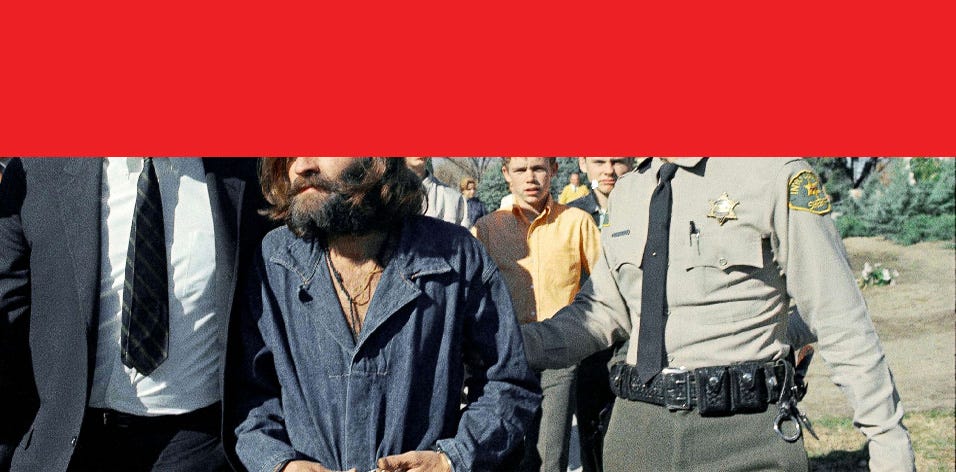

Cady Noland reached artistic maturity in mid-1980s New York. From the beginning, her work confused and disturbed. There was no clear precedent for her early sculptures — everyday objects (metal pipes, police holsters, mobility walkers, handcuffs) scattered on the floor or attached to a metal rail. As her work evolved, it became even more confrontational, with chain-link fences and barricades choking off her exhibition spaces. On metal sheets she printed news photos and articles about Patty Hearst, Lee Harvey Oswald, Geraldo Rivera, the Manson Family. Then in 1993–94, with fabricated aluminum works like Your Fucking Face, Noland found her iconic sculptural form: a functioning replica of a pillory — ye olde contraption for public punishment — complete with holes for the offender’s legs, arms, and head.

In a 1989 artist’s statement, Noland explained the genesis of her sculptures: “Working with objects instead of representations of them I began to think of the instances in which people are treated as objects. Since the psychopath objectifies people and psychopaths tend to act out the undercurrent of a culture’s latent principles, I became interested by extension in the psychopathic imperative of the American opportunist. As an exercise, in some of my pieces, I have made an exaggerated occasion of ‘opportunity’ as an end in itself. This is an attempt to realize psychopathic behavior, and to share my understanding of it with other people.”

“The game is a synthesis of tactics, played out in the social arena, where advantage can be gained in an oblique way. Demonstrations of the game are available on TV shows like Dynasty and Dallas.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

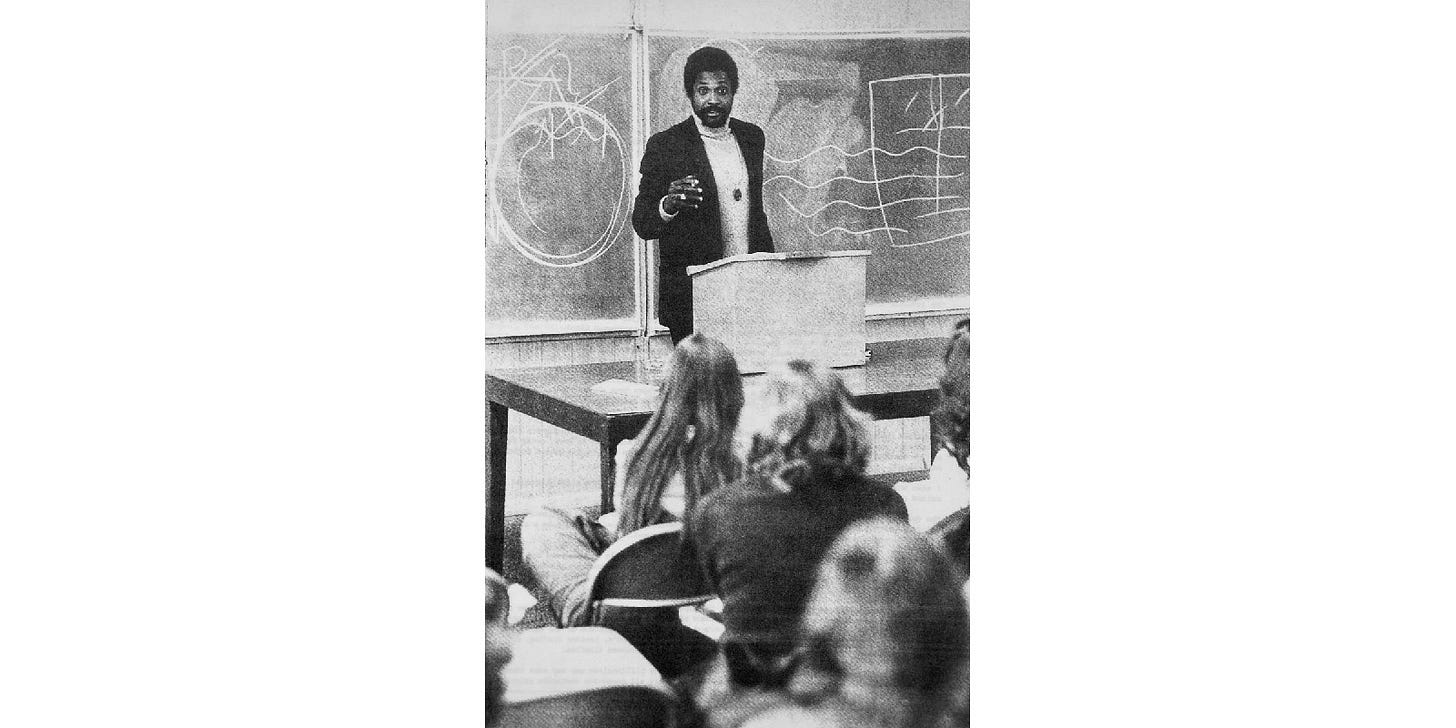

Cady Noland was born in 1956 and spent her early childhood in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC. Her mother, née Cornelia Langer, was the daughter of a prominent Senator. Noland’s father, the abstract painter Kenneth Noland, belonged to a psychotherapy cult that endorsed promiscuity and discouraged interacting with one’s children. After he and Cady Noland’s mother divorced in 1957, he dated Mary Pinchot Meyer, herself recently divorced from a high-level CIA operative, Cord Meyer. (I don’t have space for Mary Pinchot Meyer’s story, but here are the key points: shortly after Meyer’s relationship with Kenneth Noland, she began an intense love affair with John F. Kennedy that lasted his entire presidency. Less than a year after his assassination, she was shot execution-style while out on a stroll.) During the 1950s and early 1960s, the Nolands’ neighborhood was the residential locus of Cold War political power. A line drawn between the Kennedys’ various Georgetown residences would encircle the Noland home, and Cord Meyer was one of many CIA spooks living in the neighborhood. All of which is to say that, between the clandestine political maneuvering, the extramarital affairs, and the unsolved assassinations, Cady Noland had a front-row seat to the operations of power, corruption, and lies. She and her mother moved to New York sometime in the 1960s, and in the 1970s she attended college at Sarah Lawrence. There she was taught by the sociologist Stephen N. Butler, whose course helped shape her thinking about the exercise of power in America.

“Although he would pretend to play the game to the last, and he would viciously press a peer to take on genuinely life-threatening risks, the psychopath always saves his own skin. The psychopath may court death, but it is someone else’s.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

You’ve probably noticed I haven’t included any images of Noland’s work here. Noland largely withdrew from art in the 1990s, and she spent the 2000s and 2010s not only severing her ties to the art world but also obstructing attempts to exhibit, sell, or even publish her work. In 2004 I started working at Phaidon, where the first book I proposed was a monograph on Noland. I spent the next few years attempting to reach her through various intermediaries, but my efforts amounted to nothing. (One of those intermediaries, Richard Flood, was already in talks with Noland about a survey exhibition of her work to inaugurate the New Museum’s shiny new building on Bowery. When he and I spoke a few months later, this idea had morphed into a thematic group show with Noland’s work at its center. Soon she pulled out entirely. But the exhibition proceeded without her work, under the title “Unmonumental”, an unspoken tribute to her influence on an entire generation of sculptors.)

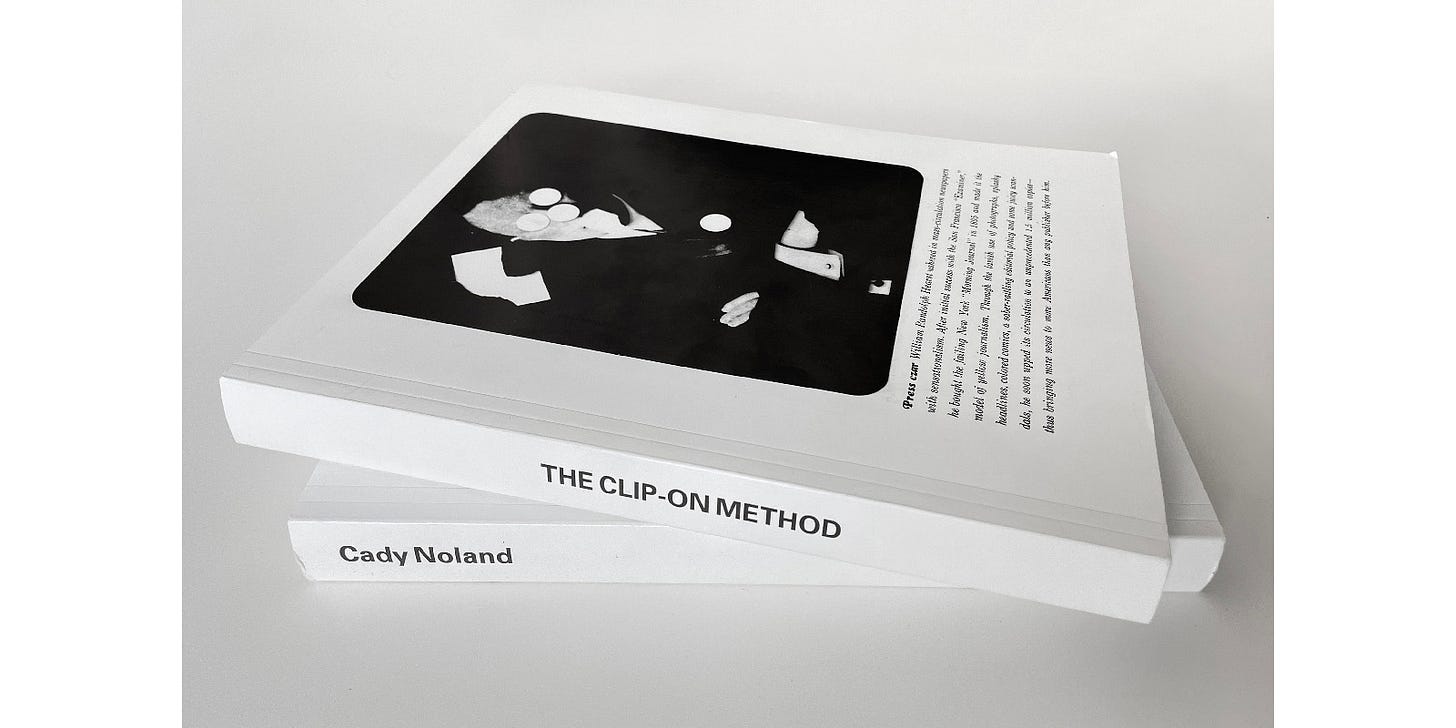

Noland still maintains careful control of her work, refusing exhibition requests and sometimes wielding her copyright to block reproductions of her art online and in print. In the last few years, though, she has come back around to the art world — though strictly on her own terms. She finally agreed to participate in a major survey exhibition, which opened at the Museum für moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt in 2018. Having once said she would shoot Larry Gagosian if he ever showed her art without permission, she agreed to a solo exhibition at his 75th & Park location. It was her largest presentation of new work in decades. And most exciting of all — for me anyway — in 2021 she finally published her first monograph.

She made the book not with Phaidon or any other publisher but completely on her own. (Rhea Anastas was co-editor and co-publisher, with typesetting and production by Will Holder and help from Robert Snowden.) Released in 2021 exclusively at Galerie Buchholz, THE CLIP-ON METHOD Cady Noland is a 596-page book in two volumes, with more than two hundred images of her work spanning four decades. Noland’s design for the book is as understated as humanly possible: letter-size format, paperback binding, no color (aside from a small handful of exhibition photos), one typeface (a monospace typewriter font). But after a decades-long drought of information and images, this publication was a cause for celebration among Noland fans. Like her work, the book’s deadpan presentation conceals a rich trove of insights.

The texts in the first volume (Cady Noland) are writings by the artist:

three exhibition statements from 1989

a visual feature for Artforum from 2002

most importantly, “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”, a remarkable essay she wrote for an academic conference in 1987 and revised in 1992 for Documenta 9.

The second volume, THE CLIP-ON METHOD, reproduces texts from different sources on a variety of non-art topics. It opens with this photo of Stephen N. Butler, her sociology professor, then continues with his proposal to diversify Sarah Lawrence’s faculty in the 1970s (it was rejected) and, perhaps most interestingly, his syllabus for a 2013 course he taught at CUNY called “Predators, Prey, and Social Mobility”. This entire volume of her book, in fact, resembles a course reader, including several sociology essays I could imagine Butler assigning in his courses: “Weapons as Aggression-Eliciting Stimuli”, “Symbols of Power: Furniture”, and “Paranoid Style”. But the essay that’s most relevant here, and which Noland references in “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”, is Ethel Spector Person’s “Manipulativeness in Entrepreneurs and Psychopaths”, originally published in a 1986 book called Unmasking the Psychopath.

“The game is a machine composed of interconnected mechanistic devices. These devices facilitate bad-faith interaction. A con or snow job is the site at which X preys on the hopes, fears, and anxieties of Y for ulterior motives and/or personal gain.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

Noland’s work has often been compared to Andy Warhol’s. There are clear overlaps, particularly in technique (screen-printed news photos) and themes (America’s love of shopping and celebrity action deaths). You could say that both artists are interested in psychopathy, but — as I’ll get to in a moment — it’s complicated.

Warhol was arguably the first postmodern artist. Mass-market commodities not only provided him with subjects, they also served as a model for his entire art practice. In New York at that time, painting was defined by Abstract Expressionism: a physical struggle with one’s metaphysical subjectivity. But Warhol’s work looked like it was painted by someone with as much of an opinion about art as a label-printing machine has about Campbell’s soup. His work embodied the logic of the spectacle, driven by the principle that any product of mass culture was worthy of contemplation, sans judgment. As the old saying goes, “that which appears is good, that which is good appears.”

In interviews, Warhol evaded questions about the meaning of his art — or, really, his position on any issue, artistic, social, or political — responding instead with empty platitudes. Many people have described interacting with Warhol as boring, (“I like boring things,” he once said), and his diaries are emotionally flat, filled with rote transcriptions of his daily activities. But one thing you do learn from his diaries is that he cared a lot about lucre: “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”

To achieve this end, Warhol transformed his personal life into an instrument of his art-as-business. As Isabelle Graw wrote in a 2010 essay on Warhol, “If the world of one’s private life looks increasingly similar to the world of one’s professional life, then society as a whole can be regarded as a ‘factory society’ (Negri/Hardt) in which life goes to work. The leading productive forces in such a ‘factory society’ are communication skills, cooperation, teamwork, and flexibility.” Sounds an awful lot like the typical twenty-first-century job: unbounded, exhausting, precarious.

In this sense, Andy Warhol was not just the first postmodern artist; he was the first neoliberal artist. His key innovation was to make his art, life, and commerce coextensive. His artist’s eye was focused not on traditional concerns, like expression or representation, but instead on production, branding, merchandising, promotion, and celebrity. He called his studio the Factory and ran it like a tech startup. The people working around him, the ones who helped him develop ideas and who acted in his films and realized his artworks, did so mostly just for the thrill of being there. And they were expendable. During the early years of the Factory, when it was a buzzing hive of nonstop happenings and parties, Warhol supplied his employees with amphetamines so that they would keep on grinding until they burned out or broke down, at which point he would drop them without so much as a COBRA plan.

You might say Andy Warhol invented founder mode.

“The psychopath is arrested in an epistemological era associated with the childhood ages of six to fourteen. […] The world is polarized into two camps: those who would satisfy his needs and those who would thwart them. If one’s needs, like the ten-year-old’s, are experienced as all-encompassing and global, then the constant campaigning on one’s own behalf has a type of logic.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

The 1960s was when the idea that every American was the CEO of their own personal brand — call it neoliberalism or post-Fordism or the age of the individual — began to take over. As an alternative to the repressiveness of earlier decades, this idea must have felt like liberation. After growing up in a society full of strict obligations, suddenly you were free to pursue your own desires. The point of life was no longer to dutifully carry out your assigned role in your school, family, community, workplace; it was to find your own happiness as an individual. Follow your bliss! Be your own boss! Make your own job! Helpfully, there was already a model for this new way of being: the artist.

By that point in history, the free-spirited artist (painter, sculptor, musician, author) had long captivated the popular imagination, blazing their own path and defying convention. When Ayn Rand reached for an ideal hero to embody the glory of individualism in her 1943 novel The Fountainhead, she invented Howard Roark, an uncompromising architect whose creative vision is so fierce it leaves a trail of destruction in its wake. Rand’s philosophy was deeply influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly his essays in Will to Power. She titled her own 1964 essay collection The Virtue of Selfishness. Those two book titles tell you all you need to know about neoliberalism and the rise of the psychopath.

The sociologist Ethel Spector Person, in her 1986 essay reproduced in Cady Noland’s monograph, points out the increasing prevalence of both psychopaths and entrepreneurs since the 1950s, adding, “These changes parallel the current rise in narcissism noted by a number of authors. They reflect the relationship of psychopathology and character to culture and, in part, stem from the erosion (or change) of culturally validated values.”

When a society’s longstanding institutions crumble away, leaving behind only profit motive and naked self-interest, what kind of behavior is incentivized? Which pathologies are rewarded?

“The game depends on investing in things which accrue in value, or in wasting things in an obvious way (but not at your own expense, only to exhibit a genuine surplus).”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

Psychopathy is considered a pathology for good reasons. You don’t want to share a home or a workplace with a psychopath. You definitely don’t want a psychopath strolling up to you in a dark parking garage.

Regular people (non-psychopaths) habitually behave in a way that keeps society functioning and mostly pleasant. We wait our turn, we answer questions truthfully, we use our indoor voices. Psychopaths follow these rules when they need to, but they have zero qualms about breaking them. And that is the key to their success: using people’s habitual civility against them.

As any good self-defense instructor will tell you, the best way to prevail in a violent encounter is to shut it down before it starts. A predator will usually open the encounter with a criminal interview: first he violates a norm of polite behavior, (standing a little too close to you) and then gradually escalates until he deems you sufficiently easy prey. “Every time he is not slapped down (i.e., he is successful), his behavior becomes more and more extreme until finally he attacks. This is a very common interview for rapists. It is also common when you walk into the middle of a group of loitering young thugs: what ‘supposedly’ starts out with them ‘just messing with you’ escalates into a robbery or assault.”

Community activist Chad Loder recently observed that Democratic leaders (and, I would argue, news organizations, social-media platforms, and non-MAGA Republicans) have spent the past eight years failing these boundary tests: “The key to the criminal interview is that the would-be predator operates unconstrained by norms — all options are on the table for them. The predator is testing how far they can push their potential victim before getting pushback. The predator is trying to figure out ‘Can I get away with this?’ I think the fascists who are now carrying out a coup in the US have spent the last eight years conducting a criminal interview of the Democratic party. They’ve concluded, correctly, that the Democrats are incapable of making the mental shift required to do what’s necessary to defend themselves.”

As of January 20, 2025, we are now in the assault phase of this criminal encounter.

“There are those who feel their kind or type is immune from being worked over by X. Some of the most shocking moments in real life and in fiction occur when they are disabused of this synthetic notion. The major theme in film noir is that there is never a respite, in this world, from the game and its exploitations.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

There are people who want you to think the predator/prey relationship is natural. These are the same people who want you to believe that their race is superior, that poor people are lazy, that men have a right to women’s bodies. With the predator/prey framing, they release themselves from norms and create a permission structure for cruelty and violence.

Washington, DC, has long covered for, even condoned misogyny and sexual violence, but what’s new today is a political party that expressly promotes sexual predators to positions of power. When the new Secretary of Defense, a Fox News host credibly accused of sexual assault, was confirmed by Congress on January 24, Representative Joni Ernst (R-IA), herself a combat veteran and sexual-assault survivor, explained her yes vote by citing his unique suitability to oversee the world’s “most lethal fighting force”. A couple days earlier, Andy Ogles (R-TN) introduced a bill authorizing the president to invade Greenland simply because the United States is the world’s “dominant predator”. This is psychopathology as official policy.

As Ethel Spector Person points out in her essay, “The moral behavior of the ruling group tends to be more criminal than that of the ruled population, [and] the lack of morals and apparent lack of guilt characteristic of psychopaths can be found to exist among many people of power and influence.” Corruption — moral and political — is self-perpetuating. When aggression is the norm and rules are meaningless, even the predators feel they’re at risk. Ethel Spector Person again: “From the psychopath’s point of view, his behavior is not reprehensible. He usually sees himself as acting defensively in order to avoid being taken advantage of himself.”

No one is safe from the operations of the predator, as Noland herself points out in “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”: “As benefits the extreme artificiality of these devices, there is no group who is naturally the victim of this abuse. These are mechanistic devices and have nothing to do with nature.”

“X may fashion an artifact called ‘the mirror device’ with which to manipulate Y. Using the device, X cynically fashions his tastes and judgments to accord with those of Y, thus winning Y’s trust an approbation. An alignment is formed under false pretenses, but Y, hopefully, is none the wiser.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

Let’s return to the contrasts between Noland and Warhol. Most obviously, there’s Noland’s fierce antipathy to the celebrity culture that Warhol embraced. The celebrities who appear in Noland’s work are not Warhol’s glittering stars, and she has rejected the neoliberal dictum that everyone must instrumentalize their own private life by leveraging their appearance and social connections to promote their professional self. In the art world, Noland is still famous for avoiding attention. She has refused all interview requests for thirty years now, and it’s hard to find a photo of her online, or anywhere.

Noland’s work is an analysis of power, not a celebration of it. Unlike the pop and postmodern artists, Noland shows the American flag as a limp little thing, scattered among the beer cans, hubcaps, and other debris of American culture. Basically what I’m arguing is that Noland makes art about psychopathic behavior without endorsing it and without becoming a psychopath herself.

Noland’s friend Steven Parrino once described her relationship to her subject matter: “She uses emotional triggers that represent weakness. Crashed Car (Cady was in a wreck at a young age), Plane Crash Photos (Cady is afraid to fly), The Family and the SLA that kidnapped Patty Hearst (Cady has a fear of cults). What I mean is, Noland is not making arbitrary choices as a pop artist would. To pop artists, all images generated by society are equal and impersonal. Cady’s choices are highly personal; they are based on her fears, and how she chooses to deal with them. She aestheticizes her fears and tries to control them by pinning them up.”

Disaster, violence, psychopathic conmen, authoritarian cults — these fears from Noland’s youth are also our fears. But instead of lurking in the shadows at Spahn Ranch, the psychopaths now operate freely, out in the open. They’re in the C-suites and the Oval Office, ranting red-faced about woke plots while blasting a firehose of money at their own bank accounts.

“Although the psychopath displays a chilling fondness for the game and would always prefer to operate via the game, he stops short of involving himself in the honorific courting of death except by proxy. In this way his internalization of the game diverges from its rules. He is simply not involved in fair play of any sort.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

Some critics have called Cady Noland a nihilist. I’m not sure those people understand her work. Nihilist might describe Andy Warhol and his type — artists who channel our culture’s pathology into their work while embodying it in their life. (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Richard Prince also come to mind.) But I don’t think that’s what Noland is doing.

During Cady Noland’s long absence from the art world, a lot of people decided she must be mentally ill (usually the word they used was crazy). The only thing we know for sure about her withdrawal is that she refused to compromise what she believed in. As Susanne Pfeffer, the curator of her MMK exhibition, explained to The New York Times, “As a woman, when you know what you want, you are always seen as difficult. [Noland] always knew what she wanted and not, and a lot of times that was ignored. She is one of the most free and feminist people I know.”

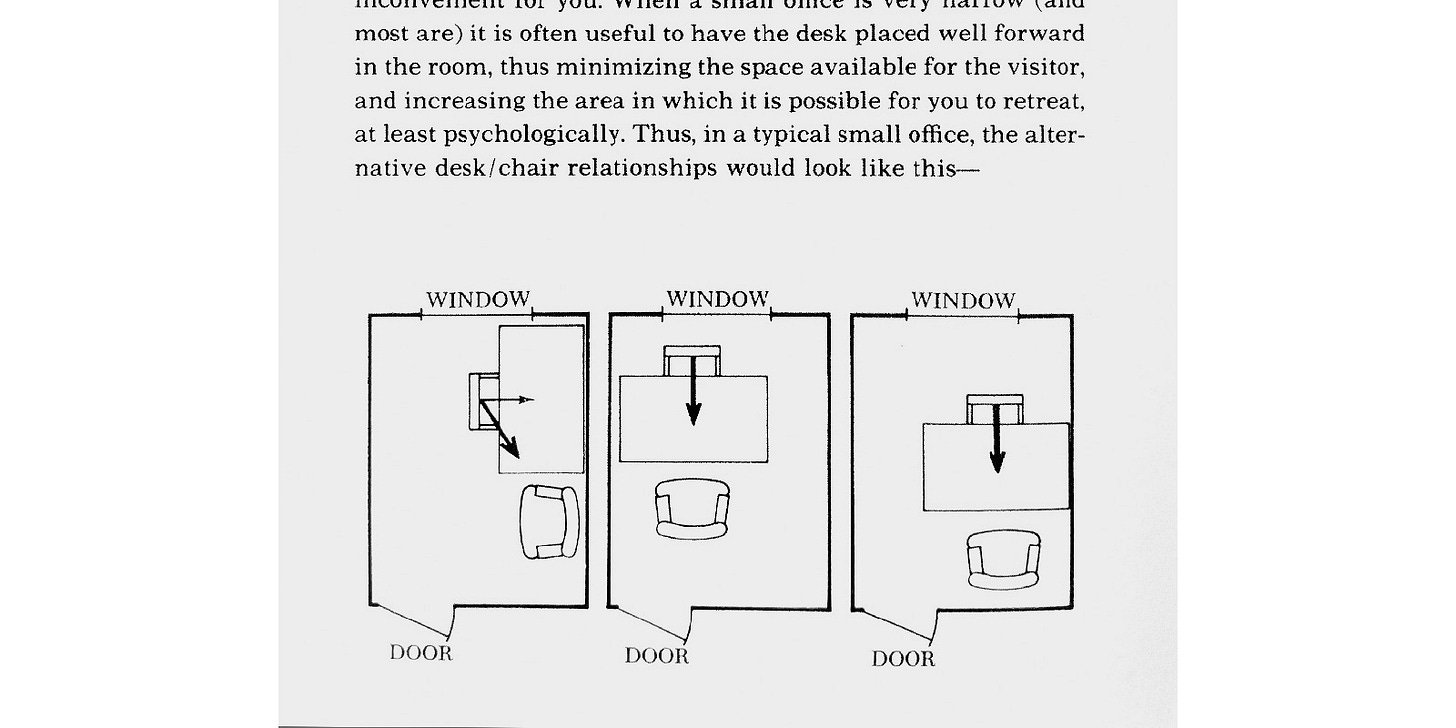

Noland understands how a carefully installed sculpture can control a room. (One essay reproduced in THE CLIP-ON METHOD is a primer on arranging your office to maximize your dominance over visitors.) I’ve heard and read many stories of her positioning a sculpture in a space, then moving it an inch, considering it, moving it another inch, and repeating this process, sometimes for several days, until she’s satisfied. This exacting approach to her work has led to disagreements and even lawsuits. At least twice, she has disavowed a collector’s restoration of a sculpture, thus reducing its potential multimillion-dollar value all the way down to zero.

My theory for why Noland withdrew from the art world is that she’d encountered one too many psychopaths and endured one too many criminal interviews. The amount of power and money in the art world has exploded since the 1980s, and now, in an age of mega galleries, billionaire collectors, and art as a speculative asset, the idea that artists hold any real power seems increasingly laughable. Sometimes the smartest move in a situation like this is to shout “Leave me the fuck alone!” and exit the parking garage.

Like calling Noland difficult, labeling her a nihilist misunderstands her relationship to her own work. The point of making art about American psychopathy is not to glorify the psychopath. It’s to reveal how he operates, to demonstrate his tactics, the same way a self-defense instructor might diagram the stages of escalation in an assault. In a 1994 interview, Noland described her work as “a critique on the psychopathic ideal. Yes, it’s the model of the entrepreneurial male whose goals excuse any and all sorts of egregious behavior if those goals meet with success.”

That word critique is important. A novelist can write about barbaric acts, monstrous characters, evil triumphing over good, but when you read their book you can tell where they stand. Making art about those topics insn’t always an endorsement. Like Noland, some of the best artists working today — like Adrian Piper, Barbara Kruger, Cameron Rowland, Kara Walker, Thomas Hirschhorn — use the products and pathologies of our culture to make formally inventive art about very heavy topics. Sometimes an artwork has values that have nothing to do with its sale price.

“It is through the ACTIONS of the psychopath, in contrast to their hollow and well-chosen words, the yawning canyon between what they do and what they say, that the depth of their disturbance and deception must be measured.”

(Cady Noland in her 1987/92 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil”)

If you’d like to see Noland’s work in person, you’ve got until the end of next week to visit her largest exhibition since the big 2018–19 survey in Germany. This one is at Glenstone, a private museum in Potomac, Maryland, and it includes a handful of her most important sculptures from 1987–94 along with the entirety of last year’s Gagosian installation, greatly expanded. It’s the first time Noland has had an exhibition in the greater DC area — though still at arm’s length from central Washington. According to a guard who happened to be working at the museum on November 6, the day after the presidential election, he could hear visitors in the exhibition sobbing when the result was announced.